The National Family Preservation Network recently released a research study that included findings from assessment tools and exit instruments.

The North Carolina Family Assessment Scale (NCFAS) was originally designed for use with a statewide IFPS program in North Carolina. It includes 5 domains that measure family functioning: Environment, Parental Capabilities, Family Interaction, Safety, and Child Well-Being.

The tool has been proven reliable and valid with dozens of IFPS programs. A later version of this tool, the NCFAS-G, includes the original 5 domains plus 3 additional domains of Social/Community Life, Self-Sufficiency, and Health. Initial reliability and validity for the NCFAS-G was established with a differential response program.

Some IFPS agencies have been reluctant to use the NCFAS-G because it had not been tested with an IFPS program. The research study included use of the NCFAS-G with 2 IFPS programs and 1 differential response program. The following is a chart showing the reliability of the NCFAS-G as used with these programs:

Reliability of NCFAS-G using Chronbach’s Alpha as the Reliability Statistic:

| NCFAS-G Domains | Intake | Closure |

| Environment | .913 | .922 |

| Parental Capabilities | .838 | .869 |

| Family Interaction | .881 | .903 |

| Family Safety | .862 | .919 |

| Child Well-Being | .894 | .869 |

| Social / Community Life | .833 | .822 |

| Self-Sufficiency | .920 | .887 |

| Family Health | .800 | .813 |

| N | 181 | 166 |

By convention and agreement among psychometric researchers and scale developers, Chronbach’s alphas above 0.8 are considered to be strong, and alphas above 0.9 are considered to be very strong.

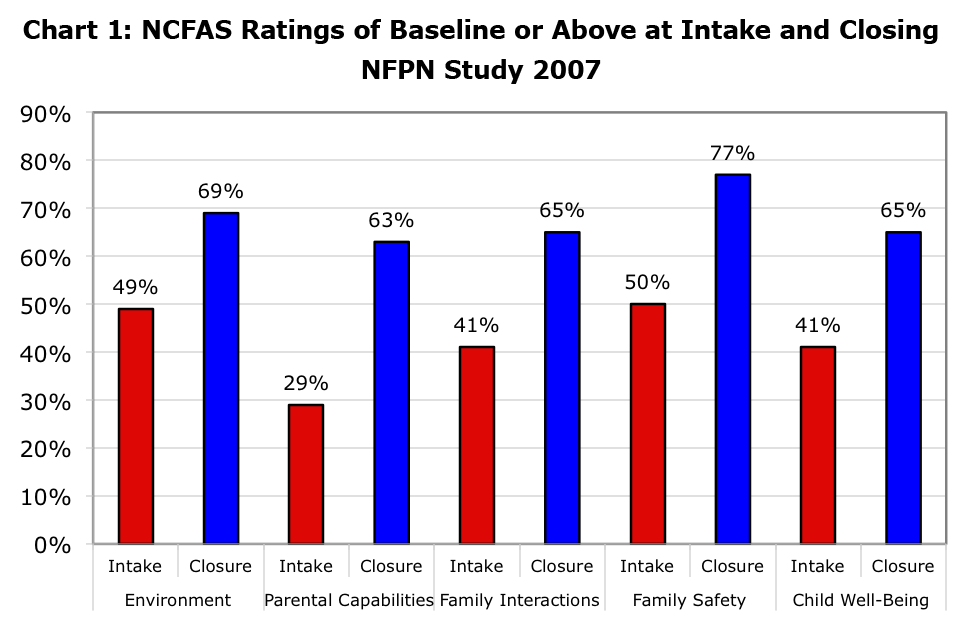

The NCFAS tools are designed to assist workers with assessing the family’s needs, prioritizing goals and services, developing a case plan, and measuring the family’s progress following delivery of services. The NCFAS tools are also used in evaluation and research. In the recent research study, the following chart shows the percentage of families functioning below baseline (adequate) at intake and at case closure:

| NCFAS-G Domains | Intake | Closure |

| Environment | 16% | 6% |

| Parental Capabilities | 30% | 8% |

| Family Interactions | 22% | 8% |

| Family Safety | 19% | 6% |

| Child Well-Being | 35% | 12% |

| Social / Community Life | 11% | 4% |

| Self-Sufficiency | 25% | 13% |

| Family Health | 28% | 8% |

| N | 184 | 172 |

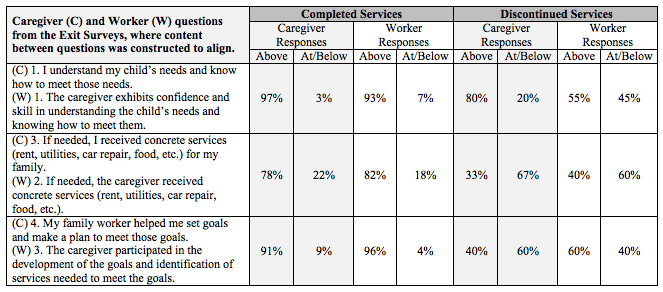

The research study also included testing of exit instruments designed by NFPN to align questions for the worker and parent(s) which correspond in general with the NCFAS assessment tools. You will note from the examples in the following chart that when families completed services, caregiver responses at termination almost mirrored the responses of the worker whereas there was more disparity between caregiver and worker when the family did not complete services:

Proportion of Responses About “Neutral” and At or Below “Neutral”

To read the full research study, visit:

http://nfpn.org/reunification/reunification-research

For more information on the assessment tools, visit:

http://www.nfpn.org/assessment-tools

_______________

Posted by Priscilla Martens, Executive Director, National Family Preservation Network