Parent education is a critical issue for the field of IFPS.

A uniform, nationwide approach to protecting children from abuse and neglect is less than 50 years old. This is helpful to keep in mind when discussing aspects of the child welfare system. The advent of a nationwide public agency system in the mid-1960’s for identification of child abuse and neglect brought with it the need for prevention and treatment.

Preventing and treating child abuse and neglect, or its re-occurrence, often focused on parenting skills, with the intent of remedying skill deficiencies. One of the earliest parenting programs, Parents Anonymous, provided support groups and taught new skills to parents. For decades, parenting classes have been the main intervention—not only offered but generally mandated by courts—for parents involved in child abuse and neglect.

A Child Welfare Information Gateway Issue Brief (2013) defines parent education:

Parent education can be defined as any training, program, or other intervention that helps parents acquire skills to improve their parenting of and communication with their children in order to reduce the risk of child maltreatment and/or reduce children’s disruptive behaviors. Parent education may be delivered individually or in a group in the home, classroom, or other setting; it may be face-to-face or online; and it may include direct instruction, discussion, videos, modeling, or other formats (California Evidence-Based Clearinghouse [CEBC], n.d. & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2009).

How does the field of IFPS address parent education?

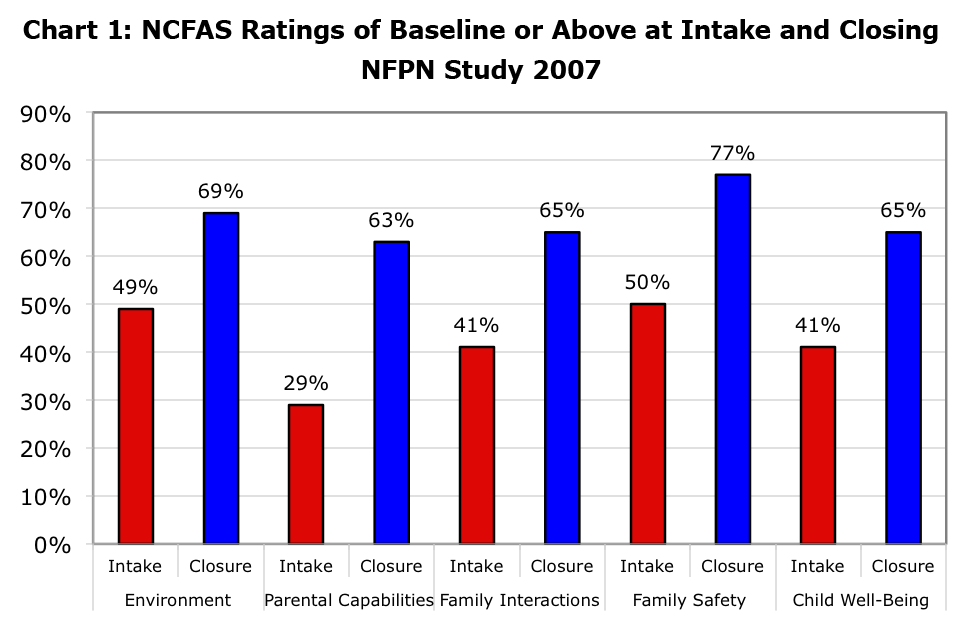

Not surprisingly, the most frequently listed need of parents referred for IFPS is parenting skills. In a multi-state study of IFPS, the NCFAS assessment tool (measures family functioning in the domains of environment, parental capabilities, family interactions, safety, and child well-being), indicated that 71% of parents had mild to serious problems in the domain of parental capabilities, significantly higher than for problems in other domains. Parental capabilities includes measures of supervision and discipline of children, parental use of drugs/alcohol, and parental support of children’s education. Over a third of the parents had moderate or serious problems in these areas.

The study found that IFPS services had the most impact on parental capabilities: at the end of interventions parents showed the highest positive gains on this domain.

What is the secret to achieving these gains?

The Child Welfare Information Gateway Brief lists, among others, the following characteristics for effective parent education programs:

- Strength-based Focus

- Family-centered Practice

- Qualified Staff

- Targeted Service Groups

- Ecological Approach

That pretty well sums up the characteristics of strong IFPS programs!

The classic book on IFPS, Keeping Families Together, says that the key is to teach parents how all people, including their children, learn. This involves three ways to facilitate learning:

- Direct instruction—presenting information

- Modeling—showing how to do something

- Contingency management—encouraging learning by rewarding desired behaviors and ignoring or (rarely) punishing behaviors that parents want to discourage

There are also specific curricula that are used in IFPS programs and other models of service. Parent education curricula are now evaluated for effectiveness and assigned ratings ranging from evidence-informed to evidence-based. Twelve curricula are listed in the Child Welfare Information Brief along with seven registries that have rated parent education programs. For details, visit:

https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubs/issue_briefs/parented/

Please share what your IFPS program has found to be effective for parent education.

_______________

Posted by Priscilla Martens, Executive Director

National Family Preservation Network